India’s vulnerability to Ebola

November 8, 2014 § Leave a comment

There is much concern about potential public health nightmare should Ebola reach the Indian shores. There is The Economist which says:

Some experts say the possibility of Ebola arriving in tropical, relatively poor and densely populated South Asia is a particularly dreadful scenario. Peter Piot, a Belgian microbiologist who helped to identify Ebola in the 1970s, told the Observer newspaper this month that he is especially worried about the state of public health in India as “doctors and nurses in India, too, often don’t wear protective gloves. They would immediately become infected and spread the virus.” Others have suggested it would be a problem that India has only two facilities capable of testing for the virus. Moreover the prevalence of malaria, dengue and other fever-inducing illnesses in India could make it especially difficult to isolate those who might show early onset of Ebola, which has similar symptoms.

The nation spends less than 1 percent of its gross domestic product on public health care. There are only nine hospital beds per 10,000 in India, compared with 41 per 10,000 in China, and doctors, nurses and lab technicians are critically lacking.

The Indian government has already shown itself incapable of dealing with lethal viral diseases. As many as 80 percent of the 30 million Indians infected with dengue fever every year never seek medical care or are turned away from hospitals whose beds are full. Ebola would quickly overwhelm such strained hospitals

If you have read enough about Ebola, you would know three things:

- That it is spread through body fluids, and not through contact or other common media of viral spread such as air or water

- That it takes several days for the disease symptoms to manifest, i.e. an infected person may seem healthy for as long as 2-3 weeks

- For those infected, it is extremely fatal and there is no cure yet

What many are anticipating (or dreading) is a nightmare scenario of an infected person arriving at cities like Mumbai or Kolkata, among the most densest cities in the world where infection spread would be manic and potentially impossible to contain. Among the chief reason why the infection spread could be fast is because the public health system is not well set to handle health crisis of this nature.

The medical workers who treat Ebola patients are among the ones who are most affected (e.g. American cases are those of doctors and nurses). Hence the worry about Indian public health workers (doctors, nurses) do not take sufficient precaution when treating patients. Unfortunately, that doomsday scenario assumes that the overall strength of public health system (infrastructure and personnel) is a direct indication of strong the nation is to fighting a health contagion. The world has just seen an example of why that is a completely false correlation: Nigeria.

Nigeria: How to fight Ebola

Let’s compare the basics of Indian and Nigerian health system: Nigeria has 400 physicians for every 1000 persons, against India’s 700 physicians/1000 persons. Nigeria has 0.4 beds per capita, while India has 0.9 beds per capita. WHO minimum recommendations for both these stats is at least 1.3 units per capita. So “the overall” health system in either countries is nowhere near the minimum level expected.

But regardless, Nigeria over last three months has managed to contain and eventually remove any threat of Ebola from the country. That success is attributed to not the robustness existing health system, but how well the government mobilised resources to muster the massive effort necessary to trace contacts and monitor the infected individuals. It is also worth noting that Nigeria’s Ebola crisis originated in Lagos, once again one of the densest cities in the world.

… Nigeria set up a centralised emergency operations centre, staffed with many public health experts who work on the polio eradication effort. It also had a first-class virology laboratory affiliated to the Lagos University teaching hospital which turned around testing and diagnoses in 24 hours. Generous government funds were allocated and quickly disbursed, says WHO. TV broadcasts by movie stars and social media were used to reassure and inform people. More than 150 people were sent out to look for contacts of people who had become ill and GPS systems in place to counter polio were used for tracking Ebola contacts. It was, said WHO, “world-class epidemiological detective work”.

So no, poor public health system does not necessarily mean an epidemic such as Ebola will spread in India if and when it lands here. What that really means is that the emergency health systems have to gear up and public awareness (while controlling fear mongering) is most important. There is detailed epidemiological account of how Nigeria avoided a far worse outbreak. Incidentally, with Nigeria declared as Ebola-free, the probability of the disease reaching Indian shores has dramatically reduced: around 90% of Indians who are in Africa reside in Nigeria.

Nightmare scenario

Health infrastructure and minimum number/quality of health workers is definitely important in fighting any serious health problem. But what is often missed that the countries that are most severely affected by Ebola are extremely poor both medically and financially. The account of how the virus spread in Sierra Leone, where it was battled largely by non-profits like Doctors Without Borders, and now more heavily by the UN, is gripping and terrifying.

What these countries also lack is a strong administrative government which can muster required resources to control such an epidemic. Even Senegal, which is worse than Nigeria in health infrastructure, has managed to avert serious breakdown.

For virus to really penetrate in India, the hypothesis is that an infected individual, who went unchecked and undocumented on entering India from any of the infected countries, seeks medical help in public health system away from any of the major medical centres in India. Where in reality, since around August, all arrivals from Western African countries have been screened. As mentioned above, majority of these arrivals are from Nigeria, a country now declared free of the virus. Around 1,100 such passengers have been screened and all have been diagnosed negative of the virus. There are three individuals who are being closely monitored, as potential risks.

That the government is further stepping up screening facilities and prepping up for disaster scenarios can only be a good thing. India remains among the major destinations of travel from Western Africa, which means it will remain under the risk of infection. But to suggest that it could be facing severe breakdown because of poor medical infrastructure is simplifying the approach to a resolution.

Rural-urban divide of Indian banking system

June 24, 2014 § Leave a comment

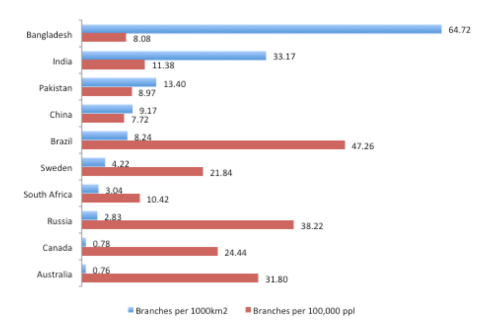

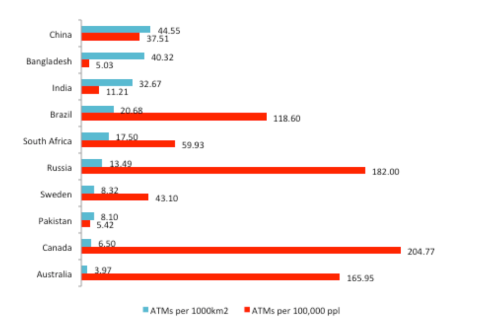

Quartz India is talking about the geographical density of two key financial infrastructure elements, bank branches and ATMs, in India. At the outset, the observation made is that the geographical reach India’s financial infrastructure is not just good, but better than several of the developed countries such as Australia and Sweden. There are couple of gaps in the analysis done here though.

First, let’s take look at the data source used: The Financial Access Survey of the IMF. It is a supply-side survey, i.e. it looks at how good the supply of financial services is in various countries. In addition to the the per unit area data (geographic density), the survey also has data on population outreach. When you look at these two datasets together, you see a much different picture.

All those countries, including India, who did so well on the geographical density perform poorly when it comes to population outreach. Ergo, even if India has infrastructure that is seemingly closer to reach, it is still not on par with the developed world in terms of financial inclusion of its population. Here it must also be said that these two infrastructure modes are in fact quite outdated (branches more so) and banks in developed countries may be decreasing their emphasis on them over the years.

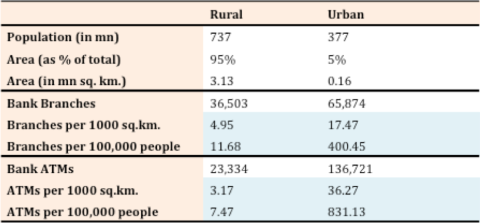

Rural vs. urban divide

In spite of the above gap, it still seems that India has a pretty good infrastructure base and just needs to work on improving the coverage of population at these outlets. But that ignores the biggest problem faced by India’s banking system (which is briefly alluded to in the Quartz article), the rural-urban divide. With the help of the Branch and ATM data available with the RBI, we can break down India’s banking infrastructure presence.

That break-up now seems to represent a lot clearer picture of how things stand when its comes to financial inclusion in India. The urban India clearly has a much better network. Although, this will most likely moderate as consumers move towards more sophisticates modes of financial transaction. Rural India, however, is woefully behind. No wonder India Post is pushing so hard to to be a bank and serve these rural areas. In that Quartz is rightly pointing out that in developed countries, people living in rural areas are likely to have much better access to banks than in India.

Note on Urban Area:

There is no direct and latest comprehensive source available which provides the urban built-up area in India. The earliest official source I found was an Urban Development ministry document of 2001, which put urban area at 2.34% of total area. Between 2001 and 2011, the urban units in India have nearly doubled while the large urban agglomerates have sprawled further. Considering this, I have also doubled the urban area to assume 5% of total area. However, common logic will dictate that the area is likely to much lesser than this. Independent sources also put the area at much lower values, although they are unlikely to be comprehensive.

Starbucks in India

May 29, 2014 § 1 Comment

Quartz has a cartographic profile of Starbucks’ global presence. Starbucks is rather new in India (its first store opened in October 2012) and has only 40+ stores today. So unsurprisingly India doesn’t figure prominently in that profile. But I bet it’s not far away from figuring into that mix. I have two purely conjectural predictions about Starbucks in India-

A. In two (max. three) years, India will be among the top ten nations in terms of stores.

Asia Pacific is clearly the focus region for Starbucks going forward, and looking at its penetration in South Korea and Japan, China, India and South-East Asia are obvious growth options. To be in the top-10 would mean around 200-250 stores, which with Starbucks’ current growth plans seem plausible

B. The National Capital Region will have the most stores

Starbucks is clearly city-focused. Of its 40+ stores in India, 2/3rd are present in Mumbai and NCR, split equally between the cities. With the store formats Starbucks is going for in India, it needs real estate- something that comes at a premium in Mumbai. In Delhi, Starbucks is still limited to central and south Delhi and Gurgaon, which means plenty of opportunities in rest of Delhi and Noida. Delhi, incidentally, also has the first Indian instance of the location bombarding that Starbucks is famous for: Delhi’s Connaught Place now has two Starbucks outlets at little over 100m distance.